Death

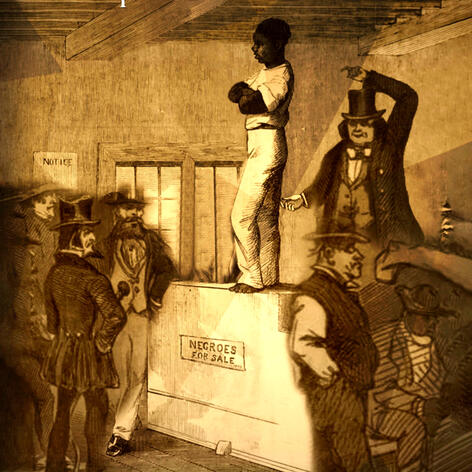

Year 1962 - Jack

It’s weird when you see death. I stared at the body and knew it had nothing inside.“Tricia, can you hear me? Oh, my God,” said Aaron.He knelt on the side of the country road, holding his girlfriend’s body and kept on like that, but I knew she no longer lived there. She’d dwelt in that body only moments before. But now she’s gone.What happens after you die? Where do you go?After seeing her vacant eyes, I asked those questions often. Tricia made a temporary home in that body and left it an empty vessel.My parents had always trusted Aaron, my older cousin. They let me go with him when they wouldn’t let me go with anyone else.All that changed, of course. Although Aaron didn’t cause the wreck, his decision led to it. He drove us to the party that night.Aaron, Tricia, and I had crashed that party, a typical rich kid’s party that occurs after the parents get away to their chateau on the French Riviera, or some such place.I’d mostly played pool upstairs while Aaron passed by occasionally. He wouldn’t let me drink or get high, which bugged me because I wanted to try both, but I appreciated him looking out for me.Across from the pool table, people sneaked into a room grinning and came out wearing bigger grins, sometimes wiping powder off their noses.Tricia’s parents had bought her a Maserati, and Aaron drove it that night for the first time. When we left the party, Tricia’s brother, who also drove a Maserati, wanted to race.

I’d seen Tricia’s brother go into that room, which made bigger grins, and told Aaron.Aaron wouldn’t race, but that didn’t stop Tricia’s brother.And Tricia wound up dead in her new Maserati.

Decisions and Consequences

Jack

Decisions and consequences, you reap what you sew, what comes around goes around, good karma, bad karma. That night of the Maserati crash opened my parents' eyes as well as my own. They realized the direction we headed as a family and the curse of wealth upon their son. They saw the real me, not their little boy but a transmutation.As much as I hurt for Aaron, I hurt worse for the Maserati. There goes my sixteenth birthday present. I’d hoped to get one just like Tricia’s when that year rolled around.What a stinking way to think.What a stinking world I live in.Will I be like everyone else?I wouldn’t have used the words “decisions” and “consequences” back then, but I started understanding the truth they represent when put together.What happened to Tricia planted a seed. What later happened to Aaron made it grow and led to a huge decision on my part. You’ll learn about that decision soon.But enough of that—here’s the rest of the story, starting with Reuben on that hotel room floor staring at me face to face on that fateful morning.

Contact

My book is still a work in progress. Any feedback would be much appreciated. If you'd like a complimentary proof in either paperback or audio, please contact me (while supplies last).